Syria: One year after the fall of Assad, the transition in al-Sharaa is marked by hope, divisions, and simmering conflict

Syria: One Year After Assad's Fall, the Transition in al-Sharaa: Between Hope, Fractures, and Simmering Warfare

By Maceo Ouitana*

On December 8, 2025, Syria commemorated the first anniversary of the fall of Bashar al-Assad, forced into exile after the lightning offensive launched from Idlib by forces united around Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. In Damascus, thousands of Syrians took to the streets, celebrating the end of more than half a century of dictatorship. But behind the scenes of jubilation, the country remains deeply fractured, caught in an uncertain transition where hope coexists with fear.

"There is a hostility, I would even say a widespread hatred, among the entire population toward the Assad regime," observes Anthony Samrani, co-editor-in-chief of L'Orient-Le Jour. A hostility fueled by decades of repression, corruption, and mass violence. A recent poll indicates that nearly 80% of Syrians support the new government, a figure largely driven by the Sunni majority, long marginalized.

One year after Ahmed al-Sharaa, the interim president, came to power, Syria is no longer a widespread battlefield. Nor is it a stabilized state. It is a country in limbo, where the war has receded without giving way to a structured peace.

An established authority, a state to rebuild.

The new government's first success is political: the collapse of the regime did not lead to chaos. Central institutions are functioning, the administration is operational, and Damascus has once again become the country's decision-making heart. This rapid stabilization contrasts sharply with the scenarios of total fragmentation feared by the end of 2024.

However, this centralization rests less on solid institutions than on a vertical power structure. The parliamentary elections held in 2025, indirect and heavily controlled, have revived a minimal parliamentary activity, without dispelling doubts about the country's political trajectory. The new Constitution, heralded as the cornerstone of the transition, is still pending.

Behind the scenes, several observers note a growing concentration of decision-making power around the interim presidency. The promise of an inclusive state is clashing with a more pragmatic reality: governing quickly, maintaining order, and reassuring international partners. "It is certainly too early to talk about the democratization of Syria," says Patricia Karam, a researcher at the Arab Center in Washington, "but the country is at a pivotal moment: it could move toward more participatory governance, or relapse into a form of authoritarianism." Security: the end of total war, not of violence

On the security front, the contrast is striking. Barrel bombs, Russian bombings, and indiscriminate airstrikes are a thing of the past. "Compared to the enormous carnage of the civil war, the situation can be considered more or less under control," analyzes Dorothée Schmid, head of the Turkey/Middle East program at IFRI. Violence has significantly decreased in major cities. Damascus, Aleppo, and Homs are experiencing a form of relative normalization.

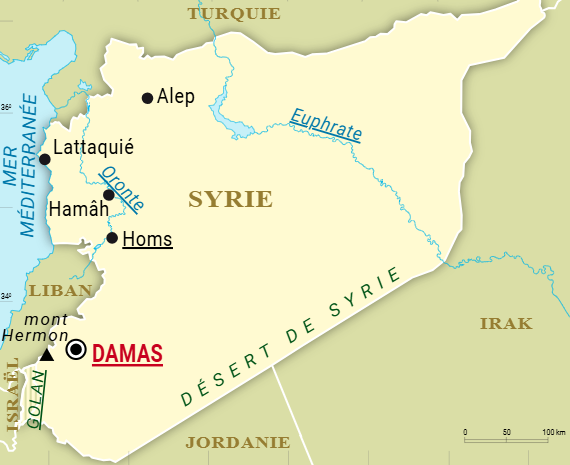

But this lull masks a fragile security landscape. The UN Security Council refers to a "fragmented security landscape," marked by localized clashes, sectarian reprisals, and the resurgence of armed groups. Localized clashes persist, particularly in the north and east of the country. The Syrian Democratic Forces, dominated by the Kurds, retain control of large swathes of territory in the northeast, which remain outside the direct authority of Damascus.

In these gray areas, Islamic State cells are attempting to regroup. Without regaining its former territorial capacity, the group is exploiting the weaknesses of the transition to carry out targeted attacks, reminding everyone that the jihadist threat has not disappeared with the fall of Assad.

Minorities and Memory: The Central Fault Line

The main fracture in post-Assad Syria is not military, but social and communal. While a Sunni majority expresses relief at the fall of the regime of the man known as "the Butcher of Damascus," minorities (Alawites, Druze, Christians) are experiencing this period with profound anxiety. Often associated, sometimes wrongly, with the former regime, they fear reprisals and denounce targeted violence. "They are being made to bear the weight of decades of dictatorship," emphasizes Anthony Samrani.

The issue of transitional justice crystallizes these tensions. Two commissions have been created: one on the disappeared, the other on the crimes of the Assad regime. While the first is progressing slowly, the second is struggling to gain traction due to a lack of clear political support. Human rights NGOs point to an incomplete justice system, focused on the crimes of the former regime and silent on those committed by other armed groups.

Without a fair reckoning with the past, the risk is that of a superficial peace, incapable of healing the wounds of a war that has claimed nearly 700,000 lives.

A depleted economy, a society on its last legs

On the economic front, the situation is dire. More than two out of three Syrians live below the poverty line. Outside the capital, infrastructure is often destroyed or out of service: damaged water networks, intermittent electricity, hospitals and schools in need of reconstruction.

Nearly three million Syrians have returned since the end of the fighting. Many are discovering neighborhoods in ruins, occupied homes, or nonexistent property titles. Land disputes are multiplying, making reconstruction as much a social issue as a material one.

"Syrians are breathing a sigh of relief, but daily life remains extremely difficult," summarizes a regional analyst who spoke to AFP. In short, the fall of Assad has freed up political space, but has not yet tangibly improved living conditions. A Conditional Return to the International Stage

It is on the diplomatic front that the change is most dramatic. In one year, Syria has emerged from its isolation. Reopened embassies, official visits, contacts with major powers: the interim government has embarked on an active strategy of normalization. The meeting between Ahmed al-Sharaa and Donald Trump, the first visit by a Syrian leader to the White House in decades, symbolizes this shift. But this rehabilitation remains conditional. Israeli incursions into the south of the country and the fragile regional balance serve as reminders that Syrian sovereignty remains partial.

An Open Transition, Without a Clear Path

One year after the fall of Bashar al-Assad, Syria has undeniably turned a page in its history. But it has not yet written the next. "Syria has made giant strides in one year, and at the same time, no fundamental problem has been resolved," summarizes Anthony Samrani. Between authoritarian stabilization, slow institutional reconstruction, and the risk of local unrest, the country is moving forward without a clearly defined compass.

The central question remains: will Syria be able to transform the end of a dictatorship into the lasting foundation of a legitimate state, or will the transition become bogged down in an unstable limbo? As 2026 dawns, Syria's future remains open… and profoundly uncertain.

* Maceo Ouitana is a journalist and contributor to FEMO.